#%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'svg'

from pylab import *

The Lagrange interpolation polynomial of degree N N N

p ( x ) = ∑ j = 0 N f ( x j ) ℓ j ( x ) where ℓ j ( x ) = ∏ i = 0 , i ≠ j N ( x − x i ) ∏ i = 0 , i ≠ j N ( x j − x i ) p(x) = \sum_{j=0}^N f(x_j) \ell_j(x) \qquad \textrm{where} \qquad

\ell_j(x) = \frac{\prod\limits_{i=0,i\ne j}^N (x-x_i)}{\prod\limits_{i=0,i \ne j}^N(x_j - x_i)} p ( x ) = j = 0 ∑ N f ( x j ) ℓ j ( x ) where ℓ j ( x ) = i = 0 , i = j ∏ N ( x j − x i ) i = 0 , i = j ∏ N ( x − x i ) There are some issues in computing it as written above.

The denominators in ℓ j \ell_j ℓ j x x x x x x p ( x ) p(x) p ( x ) O ( N 2 ) O(N^2) O ( N 2 ) O ( N ) O(N) O ( N )

Also, if we add a new data pair ( x N + 1 , f N + 1 ) (x_{N+1},f_{N+1}) ( x N + 1 , f N + 1 )

Moreover, the numerical evaluation is also unstable to round-off errors (See page 51 in Powell, Approximation theory and methods, 1981.)

These problems can be overcome by using alternate forms of Lagrange interpolation Berrut & Trefethen, 2004 Trefethen, 2019

7.3.1 Improved Lagrange formula ¶ Define

ℓ ( x ) = ω N ( x ) = ( x − x 0 ) ( x − x 1 ) … ( x − x N ) w j = 1 ∏ k = 0 , k ≠ j N ( x j − x k ) = 1 ℓ ′ ( x j ) , j = 0 , 1 , … , N \begin{gather}

\ell(x) = \omega_N(x) = (x-x_0)(x-x_1) \ldots (x-x_N) \\

w_j = \frac{1}{\prod\limits_{k=0, k \ne j}^N (x_j - x_k)} = \frac{1}{\ell'(x_j)}, \qquad j=0,1,\ldots,N

\end{gather} ℓ ( x ) = ω N ( x ) = ( x − x 0 ) ( x − x 1 ) … ( x − x N ) w j = k = 0 , k = j ∏ N ( x j − x k ) 1 = ℓ ′ ( x j ) 1 , j = 0 , 1 , … , N The Lagrange polynomials can be written as

ℓ j ( x ) = ℓ ( x ) ℓ ′ ( x j ) ( x − x j ) = ℓ ( x ) w j x − x j \ell_j(x) = \frac{\ell(x)}{\ell'(x_j) (x - x_j)} = \ell(x) \frac{w_j}{x-x_j} ℓ j ( x ) = ℓ ′ ( x j ) ( x − x j ) ℓ ( x ) = ℓ ( x ) x − x j w j and the interpolant is given by

p ( x ) = ℓ ( x ) ∑ j = 0 N w j x − x j f j p(x) = \ell(x) \sum_{j=0}^N \frac{w_j}{x-x_j} f_j p ( x ) = ℓ ( x ) j = 0 ∑ N x − x j w j f j This is called the first form of barycentric interpolation formula and is due to Rutishauser. For each x x x

calculation of { w j } \{w_j\} { w j } O ( N 2 ) O(N^2) O ( N 2 ) x x x

calculation of ℓ ( x ) \ell(x) ℓ ( x ) O ( N ) O(N) O ( N )

calculation of the other term requires O ( N ) O(N) O ( N )

so the complexity of this formula is O ( N ) O(N) O ( N ) w j w_j w j O ( N ) O(N) O ( N ) ( x N + 1 , f N + 1 ) (x_{N+1},f_{N+1}) ( x N + 1 , f N + 1 )

The total cost of updating the formula is O ( N ) O(N) O ( N )

Since ℓ j \ell_j ℓ j

1 = ∑ j = 0 N ℓ j ( x ) = ℓ ( x ) ∑ j = 0 N w j x − x j ⟹ ℓ ( x ) = 1 ∑ j = 0 N w j x − x j 1 = \sum_{j=0}^N \ell_j(x) = \ell(x) \sum_{j=0}^N \frac{w_j}{x-x_j} \limplies

\ell(x) = \frac{ 1 }{ \sum_{j=0}^N \frac{w_j}{x- x_j} } 1 = j = 0 ∑ N ℓ j ( x ) = ℓ ( x ) j = 0 ∑ N x − x j w j ⟹ ℓ ( x ) = ∑ j = 0 N x − x j w j 1 the interpolant can be written as

p ( x ) = ∑ j = 0 N w j x − x j f j ∑ j = 0 N w j x − x j p(x) = \frac{ \sum_{j=0}^N \frac{w_j}{x-x_j} f_j }{ \sum_{j=0}^N \frac{w_j}{x- x_j} } p ( x ) = ∑ j = 0 N x − x j w j ∑ j = 0 N x − x j w j f j which is called the second form of barycentric formula . This has same complexity as the previous form. Higham, 2004

7.3.3 Weights ¶ For special node distributions, we can simplify the weight calculation and obtain explicit expressions, as shown in the next sections.

7.3.3.1 Equispaced points ¶ If we have N + 1 N+1 N + 1 [ − 1 , + 1 ] [-1,+1] [ − 1 , + 1 ] h = 2 N h = \frac{2}{N} h = N 2

w j = ( − 1 ) N − j ( N j ) 1 h n n ! w_j = (-1)^{N-j} \binom{N}{j} \frac{1}{h^n n!} w j = ( − 1 ) N − j ( j N ) h n n ! 1 Since the weights appear both in numerator and denominator, we can remove any factor independent of j j j

w j = ( − 1 ) j ( N j ) w_j = (-1)^{j} \binom{N}{j} w j = ( − 1 ) j ( j N ) If the interval is [ a , b ] [a,b] [ a , b ] w j w_j w j 2 N ( b − a ) − N 2^N (b-a)^{-N} 2 N ( b − a ) − N w j w_j w j

max j ∣ w j ∣ min j ∣ w j ∣ ≈ 2 N \frac{\max_j |w_j|}{\min_j |w_j|} \approx 2^N min j ∣ w j ∣ max j ∣ w j ∣ ≈ 2 N This leads to ill-conditioning and Runge phenomenon. This is not a consequence of the barycentric formula, but is intrinsic to interpolation using equispaced data.

7.3.3.2 Chebyshev points of first kind ¶ The points and weights are given by

x j = cos ( 2 j + 1 2 N + 2 π ) , w j = ( − 1 ) j sin ( 2 j + 1 2 N + 2 π ) , j = 0 , 1 , … , N x_j = \cos\left( \frac{2j+1}{2N+2} \pi \right), \quad w_j = (-1)^j \sin\left( \frac{2j+1}

{2N+2} \pi \right), \quad j=0,1,\ldots,N x j = cos ( 2 N + 2 2 j + 1 π ) , w j = ( − 1 ) j sin ( 2 N + 2 2 j + 1 π ) , j = 0 , 1 , … , N These weights vary by factors of O ( N ) O(N) O ( N )

max j ∣ w j ∣ min j ∣ w j ∣ ≈ sin ( 2 ( N / 2 ) + 1 2 N + 2 π ) sin ( 2 ( 0 ) + 1 2 N + 2 π ) ≈ sin ( 1 2 π ) π 2 N + 2 = O ( N ) for large N \frac{\max_j |w_j|}{\min_j |w_j|} \approx

\frac{ \sin\left( \frac{2(N/2)+1}{2N+2} \pi \right) } { \sin\left( \frac{2(0)+1}{2N+2} \pi \right)} \approx

\frac{\sin(\half\pi)}{\frac{\pi} {2N+2}} = O(N) \quad \textrm{for large $N$} min j ∣ w j ∣ max j ∣ w j ∣ ≈ sin ( 2 N + 2 2 ( 0 ) + 1 π ) sin ( 2 N + 2 2 ( N /2 ) + 1 π ) ≈ 2 N + 2 π sin ( 2 1 π ) = O ( N ) for large N not exponentially as in case of uniformly spaced points. The weights can be computed in O ( N ) O(N) O ( N )

7.3.3.3 Chebyshev points of second kind ¶ The points are given by

x i = cos ( N − i N π ) , i = 0 , 1 , 2 , … , N x_i = \cos\left( \frac{N-i}{N} \pi \right), \qquad i=0,1,2,\ldots,N x i = cos ( N N − i π ) , i = 0 , 1 , 2 , … , N and the weights are

w 0 = 1 2 , w i = ( − 1 ) i , i = 1 , 2 , … , N − 1 , w N = 1 2 ( − 1 ) N w_0 = \half, \qquad w_i = (-1)^i, \quad i=1,2,\ldots,N-1, \qquad w_N = \half (-1)^N w 0 = 2 1 , w i = ( − 1 ) i , i = 1 , 2 , … , N − 1 , w N = 2 1 ( − 1 ) N Let us interpolate the Runge function on [ − 1 , + 1 ] [-1,+1] [ − 1 , + 1 ]

f ( x ) = 1 1 + 16 x 2 f(x) = \frac{1}{1 + 16 x^2} f ( x ) = 1 + 16 x 2 1 using the Barycentric formula

p ( x ) = ∑ i = 0 N w i x − x i f i ∑ i = 0 N w i x − x i p(x) = \frac{ \sum_{i=0}^N \frac{w_i}{x - x_i} f_i }{ \sum_{i=0}^N \frac{w_i}{x - x_i} } p ( x ) = ∑ i = 0 N x − x i w i ∑ i = 0 N x − x i w i f i where the weight w i w_i w i

w i = 1 ∏ j = 0 , j ≠ i N ( x i − x j ) w_i = \frac{1}{\prod_{j=0,j\ne i}^N (x_i - x_j)} w i = ∏ j = 0 , j = i N ( x i − x j ) 1 This is the function we want to interpolate.

def fun(x):

f = 1.0/(1.0+16.0*x**2)

return f

We next write a function that constructs and evaluates the Lagrange interpolation.

# X[nX], Y[nX] : Data points

# x[nx] : points where we want to evaluate

def BaryInterp(X,Y,x):

nx = len(x)

nX = len(X)

# compute the weights

w = ones(nX)

for i in range(nX):

for j in range(nX):

if i != j:

w[i] = w[i]/(X[i]-X[j])

# Evaluate the polynomial at x

f = empty_like(x)

for i in range(nx):

num, den = 0.0, 0.0

for j in range(nX):

if abs(x[i]-X[j]) < 1.0e-15:

num = Y[j]

den = 1.0

break

else:

num += Y[j]*w[j]/((x[i]-X[j]))

den += w[j]/(x[i]-X[j])

f[i] = num/den

return f

xmin, xmax = -1.0, +1.0

N = 15 # Degree of polynomial

We first interpolate on uniformly spaced points.

X = linspace(xmin,xmax,N+1)

Y = fun(X)

x = linspace(xmin,xmax,100)

fi = BaryInterp(X,Y,x)

fe = fun(x)

plot(x,fe,'b--',x,fi,'r-',X,Y,'o')

title('Degree '+str(N)+' using uniform points')

legend(("True function","Interpolation","Data"),loc='lower center');Next, we interpolate on Chebyshev points.

X = cos(linspace(0.0,pi,N+1))

Y = fun(X)

x = linspace(xmin,xmax,100)

fi = BaryInterp(X,Y,x)

fe = fun(x)

plot(x,fe,'b--',x,fi,'r-',X,Y,'o')

title('Degree '+str(N)+' using Chebyshev points')

legend(("True function","Interpolation","Data"),loc='upper right');Let us interpolate the Runge function on [ − 1 , + 1 ] [-1,+1] [ − 1 , + 1 ]

f ( x ) = 1 1 + 16 x 2 f(x) = \frac{1}{1 + 16 x^2} f ( x ) = 1 + 16 x 2 1 using the Barycentric formula

p ( x ) = ∑ i = 0 N ′ ( − 1 ) i x − x i f i ∑ i = 0 N ′ ( − 1 ) i x − x i p(x) = \frac{ \sum\limits_{i=0}^N{}' \frac{(-1)^i}{x - x_i} f_i }{ \sum\limits_{i=0}^N{}' \frac{(-1)^i}{x - x_i} } p ( x ) = i = 0 ∑ N ′ x − x i ( − 1 ) i i = 0 ∑ N ′ x − x i ( − 1 ) i f i where the prime on the summation means that the first and last terms must be multiplied by a factor of half.

The next function evaluates the Lagrange interpolation using Chebyshev points.

def BaryChebInterp(X,Y,x):

nx = len(x)

nX = len(X)

# Compute weights

w = (-1.0)**arange(0,nX)

w[0] = 0.5*w[0]

w[nX-1] = 0.5*w[nX-1]

# Evaluate barycentric foruma at x values

f = empty_like(x)

for i in range(nx):

num, den = 0.0, 0.0

for j in range(nX):

if abs(x[i]-X[j]) < 1.0e-15:

num = Y[j]

den = 1.0

break

else:

num += Y[j]*w[j]/((x[i]-X[j]))

den += w[j]/(x[i]-X[j])

f[i] = num/den

return f

Define the function to be interpolated.

xmin, xmax = -1.0, +1.0

f = lambda x: 1.0/(1.0+16.0*x**2)

Let us interpolate on Chebyshev points.

N = 19 # degree of polynomial

X = cos(linspace(0.0,pi,N+1))

Y = fun(X)

x = linspace(xmin,xmax,100)

fi = BaryChebInterp(X,Y,x)

fe = fun(x)

figure(figsize=(8,5))

plot(x,fe,'b--',x,fi,'r-',X,Y,'o')

title("Chebshev interpolation, degree = " + str(N))

legend(("True function","Interpolation","Data"),loc='upper right')

xlabel('x'), ylabel('f(x)')

axis([-1.0,+1.0,0.0,1.1]);7.3.4 Using scipy.interpolate ¶ scipy.interpolate provides many methods for polynomial interpolation, including barycentric form.

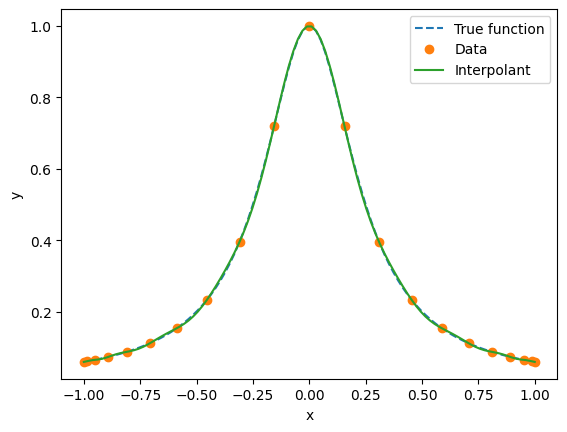

fun = lambda x: 1.0/(1.0 + 16.0 * x**2)

N = 20

xi = cos(linspace(0.0,pi,N+1))

yi = fun(xi)

x = linspace(xmin,xmax,100)

Using scipy

from scipy.interpolate import barycentric_interpolate

y = barycentric_interpolate(xi, yi, x)

plot(x, fun(x), '--', label='True function')

plot(xi, yi, 'o', label='Data')

plot(x, y, '-', label='Interpolant')

legend(), xlabel('x'), ylabel('y'), title('Degree = '+str(N));Using scipy

from scipy.interpolate import BarycentricInterpolator

P = BarycentricInterpolator(xi, yi)

plot(x, fun(x), '--', label='True function')

plot(xi, yi, 'o', label='Data')

plot(x, P(x), '-', label='Interpolant')

legend(), xlabel('x'), ylabel('y');The second form is useful to construct a representation of the interpolant once, and repeatedly use it to evaluate at different values of x x x

Interpolate f ( x ) = cos ( 4 π x ) f(x) = \cos(4 \pi x) f ( x ) = cos ( 4 π x ) x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x \in [-1,1] x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ]

f = lambda x: cos(4*pi*x)

xe = linspace(-1,1,1000)

figure(figsize=(10,10))

N = 20

for i in range(5):

x1 = linspace(-1,1,N+1)

y1 = f(x1)

x2 = cos(linspace(0,pi,N+1))

y2 = f(x2)

y1e = barycentric_interpolate(x1,y1,xe)

y2e = barycentric_interpolate(x2,y2,xe)

err1 = abs(y1e - f(xe)).max()

err2 = abs(y2e - f(xe)).max()

print("N, Error = %3d %12.4e %12.4e" % (N,err1,err2))

subplot(5,2,2*i+1)

plot(xe,y1e), plot(xe,f(xe))

text(0,0,'N='+str(N),ha='center',va='center')

subplot(5,2,2*i+2)

plot(xe,y2e), plot(xe,f(xe))

text(0,0,'N='+str(N),ha='center')

N = N + 10N, Error = 20 7.6371e-02 2.1871e-04

N, Error = 30 1.7984e-06 1.5623e-10

N, Error = 40 5.1599e-07 1.7070e-15

N, Error = 50 7.5529e-04 1.7208e-15

N, Error = 60 5.7199e-01 1.7764e-15

This function is analytic in the complex plane, so uniform interpolation should also converge. The error decreases initially but starts to rise for higher degress. This is due to large round-off errors because the barycentric weights are large. Chebyshev points do not have this problem.

Berrut, J.-P., & Trefethen, L. N. (2004). Barycentric Lagrange Interpolation. SIAM Review , 46 (3), 501–517. 10.1137/S0036144502417715 Trefethen, L. N. (2019). Approximation Theory and Approximation Practice, Extended Edition . Society for Industrial. 10.1137/1.9781611975949 Higham, N. J. (2004). The numerical stability of barycentric Lagrange interpolation. IMA Journal of Numerical Analysis , 24 (4), 547–556. 10.1093/imanum/24.4.547